Understanding the draft NPPF: Implications for air quality

- Post Date

- 16 February 2026

- Read Time

- 9 minutes

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) sets out the overarching planning policy for England and is currently subject to consultation. The December 2025 draft [1] aims to address deeper structural issues in the planning system by introducing clearer, more rules-based policy that supports growth while protecting health and the environment. Ultimately, the NPPF is intended to help unlock development and deliver the UK government’s 1.5 million homes pledge by the end of the current Parliament.

This article sets out high-level observations on how air quality is treated in the draft NPPF, and what this could mean in practice for planning decisions and air quality assessments.

Why air quality matters

Air pollution is recognised by the UK government as the largest environmental risk to public health [2]. In 2025, the Royal College of Physicians estimated that air pollution contributes to around 30,000 deaths per year in the UK and costs the economy more than £27 billion annually through healthcare expenditure and productivity losses [3].

In England (and the UK), protection from air pollution is primarily provided through legally binding numerical air quality standards, with responsibility shared between central and local government. Where exceedances occur, action is required. However, for most pollutants, these standards have remained largely unchanged for over 25 years (with PM2.5 the main exception, through the Environment Act 2021 [4]). It is widely accepted that these standards do not fully reflect current health evidence, and that adverse effects occur well below them.

This is reflected in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2021 Air Quality Guidelines, which are explicitly health-based [5]. Some argue that these guideline values are difficult for governments to implement in practice, as they must be balanced alongside other considerations such as the economy. However, in 2024 the European Union (EU) adopted a revised Ambient Air Quality Directive, introducing substantially tighter limits to be met by 2030 [6] that move closer to the WHO 2021 guidelines. While these limits do not fully align with WHO recommendations, they demonstrate that materially lower thresholds are technically and economically feasible. Following Brexit however, the UK is no longer bound by these requirements.

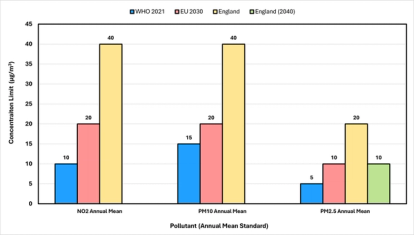

Figure 1 compares the WHO 2021 guideline values, EU 2030 limits and current UK standards for key human health pollutants. Across all pollutants, current UK standards are substantially higher – up to double the EU limits and around four times higher than the WHO guideline values. This highlights a clear regulatory gap, with people in England afforded a lower level of health protection and fewer regulatory drivers for intervention. Figure 1 also includes the Environment Act 2021 commitment to an annual mean PM2.5 limit of 10µg/m3 by 2040, which is 10 years later than the EU’s 2030 timeline.

Of course, there may be a lag before the UK considers implementing or amending its own limits. However, in its response to the Office for Environmental Protection’s (OEP) Environmental Improvement Plan progress report, the UK government explicitly rejected the recommendation to align statutory standards with either the WHO 2021 guidelines or the revised EU 2030 limits [7].

Current NPPF: A compliance-led approach

Turning to how air quality is addressed in national planning policy, the NPPF’s treatment has remained largely unchanged since its inception in 2012. Air quality is addressed within Chapter 15, ‘Conserving and Enhancing the Natural Environment’, under the broader heading of pollution (paragraphs 198 – 199) [8].

Paragraph 198 frames pollution primarily in health terms, which is a positive starting point. Its supporting text however refers to noise and lighting – pollutants without statutory limits and therefore assessed against evolving scientific evidence. Air quality is addressed separately in paragraph 199, where decision-making is explicitly tied to compliance with statutory air quality standards (those illustrated in Figure 1).

This separation is understandable, as air quality is governed by a regulated framework that the NPPF must support. However, because existing standards lag behind the current evidence base, a focus solely on compliance can result in residual health risks being overlooked, despite clear evidence that harm occurs well below statutory limit values.

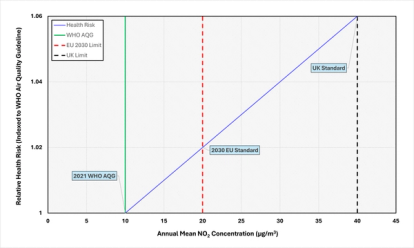

This is illustrated in Figure 2 which shows that measurable health risk persists at pollution concentrations below current UK limit values. The example focuses on annual mean NO2 concentrations, the principal pollutant of concern in UK urban areas. The limits presented in Figure 1 have been transposed to show health risk relative to the WHO guideline value. As concentrations increase along the x-axis, health risk rises progressively, including across the range below the UK standard.

This creates a tension within the planning system. While national policy promotes healthy and resilient places, air quality assessment often remains narrowly focused on compliance with standards that do not adequately protect health. As a result, opportunities to reduce exposure through site layout, design, or mitigation may be overlooked at the planning stage.

What’s changed in the new draft NPPF?

The December 2025 draft NPPF places greater emphasis on health overall, creating an opportunity to reconsider how air quality is addressed within the planning system. At the same time, this sits alongside a strong policy imperative to accelerate housing delivery.

Air quality is repositioned within a new consolidated Chapter 17, ‘Pollution, Public Protection and Security’, bringing together policy previously split between health and environmental protection. Pollution is addressed under ‘Policy P3: Living Conditions and Pollution’, which is broken into two parts.

- Policy intent: The effects of air pollution on health are explicitly referenced, suggesting stronger alignment with health outcomes and in principle greater scope to consider health-based benchmarks such as the lower WHO 2021 guideline values (Figure 1).

- Decision-making rules: When it comes to implementation, there is no reference to health. Instead, decision-making tests rely on broad concepts such as “acceptable living conditions” and subsequently re-establish a clear requirement to sustain compliance with UK air quality standards - thereby overlooking health outcomes.

This raises a key question: does the draft represent a genuine shift towards health, or does it largely reframe the existing compliance-led approach? While the NPPF is not intended to prescribe all technical eventualities, the absence of health from the decision tests risks perpetuating the current issue.

The NPPF is complemented by Planning Practice Guidance (PPG) which provides greater technical clarity [9]. However, it was last updated in 2019 and continues to place emphasis on regulatory compliance. If the NPPF is updated to reflect a stronger health focus, the PPG is overdue an update. Without this, the NPPF’s health ambitions risk remaining aspirational.

Although the WHO and revised EU limits have been rejected as statutory standards, these benchmarks can still play an important role in informing an understanding of health impacts, alongside regulatory compliance. These outcomes could feed into health impact assessments, which is becoming more common in planning. However, explicit reference to WHO 2021 guidelines or EU 2030 limits within the NPPF could create tension with wider government policy and communications.

What this means in practice

Air quality assessments are already beginning to move away from a purely binary test of compliance, reflecting growing recognition of the health evidence illustrated in Figure 2. This shift is reinforced by the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) 2024 Interim PM2.5 Guidance which explicitly advises against a sole focus on compliance and places greater emphasis on minimising pollution and population exposure [10].

In addition, the Institute of Air Quality Management has confirmed that its planning guidance will be updated to better align with current scientific evidence and to place greater emphasis on health effects [11].

The draft NPPF provides a clearer policy hook for health, and the direction of travel is becoming harder to ignore. It’s important to ensure health is a central pillar of development and air quality is not treated as a tick box.

In practice, this is likely to mean:

- Compliance with statutory air quality limits will remain necessary but may not be sufficient on its own.

- Greater policy emphasis and scrutiny to consider the health effects of pollution, even where legal limits are met.

- Earlier air quality input will be increasingly important to manage planning risk and support healthier design outcomes.

To find out more about our Air Quality services, contact our team.

Get in touchReferences

- https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-planning-policy-framework-proposed-reforms-and-other-changes-to-the-planning-system

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/air-pollution-applying-all-our-health/air-pollution-applying-all-our-health

- https://www.rcp.ac.uk/policy-and-campaigns/policy-documents/a-breath-of-fresh-air-responding-to-the-health-challenges-of-modern-air-pollution/

- https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/30/contents

- https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228

- https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/air/air-quality_en

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-response-to-the-oep-report-environmental-improvement-plan-progress-from-2023-to-2024

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-planning-policy-framework--2

- https://www.gov.uk/guidance/air-quality--3

- https://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/pm25targets/planning

- https://iaqm.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IAQM_Briefing_Land-use_Guidance_25.pdf