Are science-based targets still working?

- Post Date

- 26 August 2025

- Read Time

- 9 minutes

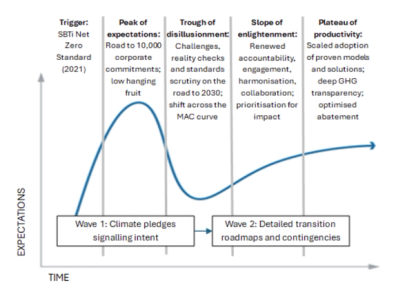

In just a few years, the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) has gone from niche to near-universal - with its Net Zero Standard becoming the benchmark for corporate climate ambition since its 2021 launch. In January 2025, the SBTi hit its own “critical mass” goal of reaching 10,000 companies committed to setting targets, and as of June, this has grown by a further 800.

But this growth has come with influence and scrutiny. Each SBTi update, from tweaks to Scope 3 rules to positions on offsets, now sends ripples across sustainability teams, climate tech providers, and investors alike. The SBTi label is a shorthand, taken by investors, lenders, and clients as a sign of the good “hygiene” of a company’s climate strategy. And beyond being a hallmark of a credible ESG strategy matrix, the underlying rules are visible in the ways that companies approach, plan for, and implement their decarbonisation strategies, permeating capital planning, supplier management, institutional engagement, and beyond.

Yet cracks are appearing. As of June 2025, nearly 800 companies, including Microsoft, Unilever, Procter & Gamble, and Walmart, have recently dropped their commitments to setting long-term net zero targets under the SBTi rules. Scope 3 uncertainty, technological unknowns, and doubts about feasibility are among the key reasons. Scope 3 challenges, unknown technological development pathways, and overall lack of certainty in ability to achieve the target cited as the greatest barriers [1]. The recent collapse of the Net Zero Banking Alliance also underlines the fragility of stated climate aspirations to a changing political and economic context.

With 2030 on the horizon, what does this mean for companies that have set or are thinking about setting science-based targets?

Is “science-based” decarbonisation feasible for most companies?

A colleague recently described SBTi as a "Ponzi scheme", with Scope 3 aspirations passed along complex supply chains looking for someone to action them. As companies cascade climate targets to their suppliers, they encounter a host of practical pain points in decarbonising value chains, many of which are glossed over during the (mostly) straightforward early-stage of target validation.

In particular, long-term net zero and Scope 3 targets often become faith-based exercises. They depend on the hope that technologies will mature, infrastructure will emerge, and policy will catch up. And as is clear from public disclosures, many companies take the plunge on SBTs without seriously stress testing some of the sensitive assumptions that lie on the road to net zero emissions. Companies also jump into these commitments with heavily estimated baselines, making it difficult to measure and manage against these targets.

This creates a tension between what companies can directly control and what lies beyond their influence. Navigating that gap takes different forms: some organisations lead with rigour and realism, others with optimism or blind spots. Corporates approach these questions with different levels of rigour, scepticism, optimism, and faith. And there are also regional differences, with the different political and legal context in the United States and Europe among the factors that set the tone for how these conversations play out.

At its core, the challenge comes down to a few fundamental questions:

- Can companies get the data they need to measure and manage change?

- Can they reasonably influence Scope 3 emissions within their value chain?

- And who should bear the cost of transition, when carbon remains inconsistently priced and markets offer few direct incentives?

If these fundamentals are overlooked, then are we setting voluntary frameworks and their participants up to fail?

If a climate pledge falls in the forest…

Apparently, not. A Harvard and UC Berkeley study [2], of 1,041 firms with climate targets ending in 2020 found that:

- 61% met their goals

- 31% quietly dropped them

- 9% reported failure

Only three of the failed firms drew media attention, and researchers found no significant market response.

So far, the SBTi’s role has been that of quality controller on the target production conveyor. Its validation process is trying to ensure that the baseline GHG inventory and target components are up to spec, but without a compliance or enforcement role during the life cycle of the pledge. The problem with this is that without accountability, firms may lack sufficient incentives to pursue genuine decarbonisation efforts. In allowing companies to quietly shuffle failed commitments under the rug, we also lose learnings from these failures that might ultimately unlock some of the obstacles that all participants know exist.

Yet the impact of SBTs is real. Companies that commit tend to reduce emissions significantly over time. And with 76% of listed companies still outside the system, the pressure to expand credible climate action remains.

If a similar trend is followed for those targets expiring in 2030, then some 2,300 companies will fail to meet their cornerstone climate change commitment (of 6,126 targets currently due to expire in that year), many of them large corporates. This has the potential to be awkward for the initiative, and for how voluntary sustainability commitments are viewed more broadly. And yet, three-quarters (76%) of all listed companies have not set science-based targets at all, and 42% have no form of climate commitment [3]. There is evidence that the adoption of SBTs does lead to significant subsequent carbon reduction, even if this takes time to manifest [4].

The road ahead: Net Zero Standard 2.0

The SBTi has started consulting on proposed changes as it looks to set the ground rules for the 2030s with its Net Zero 2.0 Standard (due in 2027). However, as trialled by the debate around accountable measures and carbon credits, balancing the views of all stakeholders is likely to be impossible. These updates won’t, and shouldn’t be expected to, fix all the corporate challenges - many reflect broader realities that no sustainability standard can solve:

- Reaching net zero will be difficult and require upfront investment [5]

- Climate policy often lags behind national commitments [6]

- Climate technologies need more financing and risk-taking to scale [7]

- GHG accounting rules aren’t optimised for Scope 3 tracking [8]

And while some companies are now pursuing climate strategies outside the framework, the SBTi remains relevant:

- It provides a shared language on terms like “net zero” and offsets, offering clarity in an increasingly fragmented green claims space.

- Its label still signals credibility to investors, lenders, and boards, and is a gold standard for sustainability-linked finance. It’s why having a science-based target has become a common procurement ask, and why this is a gold standard indicator for sustainability linked loans.

- It acts as a catalyst for cross-functional alignment and engagement, prompting organisations to integrate climate KPIs into financing, incentive structures, strategy, industry collaborations, and advocacy.

In many ways, corporate climate commitments are plotting the Gartner “hype cycle”. Following the excitement around 2021’s Net Zero Standard, the SBTi is 10,000 commitments deep into its first wave of climate pledges, where the emphasis has been on signalling intent, on building to a critical mass, and real-world testing these new rules. The recent challenges, criticisms, and departures by a few high-profile corporates setting their strategies outside of this framework can be interpreted as a sign that early-adopters (those whose targets matured in 2020 to 2025) are working through and reacting to the realities of these pledges. Expect this to continue towards 2030. What is required to move forward is a shift towards accountability and the mapping out of detailed plans, including contingencies for uncertain scenarios (i.e., transition planning).

As we pass this first peak, companies should prepare for standards to evolve and tighten towards more nuanced, shorter-term, action-oriented targets. Navigating this will require us to focus on climate progress and proof points, rather than perfect reporting results. This requires companies to find comfort in setting goals they may not be able to achieve and requires stakeholders to accept these less than perfect results. This will be challenging in some regions, but it is better to move forward imperfectly than not at all.

Advisory Digest

Enjoyed this article? For more like it, get SLR's quarterly sustainable business briefing straight to your inbox.

Sign Up

--------------------------------------

References:

[1] Business Ambition for 1.5C Campaign (2024): Final Report. Accessed at: https://files.sciencebasedtargets.org/production/files/SBTi-Business-Ambition-final-report.pdf

[2] Jiang, X., Kim, S. & Lu, S. Limited accountability and awareness of corporate emissions target outcomes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 279–286 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02236-3

[3] MSCI Sustainability Institute (November 2024): Net Zero Tracker. Accessed at: https://www.msci-institute.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/2024-November-MSCI-Net-Zero-Tracker-21Nov.pdf

[4] Li, J., Peng, X., & Zhang, H. The role of science-based targets on carbon mitigation: Addressing the tension between net zero anxiety and economic growth. The British Accounting Review, 57:2 (2025). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0890838924002713

[5] World Economic Forum (December 2024): Net-Zero Industry Tracker 2024 Edition. Accessed at: https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Net_Zero_Industry_Tracker_2024.pdf

[6] Climate Action Tracker (November 2024) estimates that current policies and action put us on course for 2.7C by 2100 (2.2-2.4C). Accessed at: https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-thermometer/

[7] We’re 0.3% of the way towards the 100 Gigatons of annual Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) capacity that the National Academy of Sciences estimates we will need by 2050 to meet the Partis Agreement. https://www.cdr.fyi/

[8] See, for example, the E-Liability proposals. Accessed at: https://www.wri.org/technical-perspectives/e-liabilities-vs-ghg-protocol-emissions-reporting

Recent posts

-

-

Unlocking value through solar PV repowering: A focus on module replacement and DC/AC optimisation

by David Fernandez

View post -