PFAS - implications on field work

- Post Date

- 24 February 2023

- Read Time

- 4 minutes

There is a significant and growing body of evidence on the prevalence and challenges associated with managing risk and exposure to per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in the environment.

It is relatively well known that PFAS were first used in firefighting foams since the 1940’s and have since been used in a wide variety of commercial and industrial applications, especially since the 1960’s. As a result of the manufacture and accidental release from these applications, PFAS have predominantly entered into the water environment from various point and diffuse sources (fire fighting foams, landfills, effluent treatment, industrial and textile coating manufacture, food packaging), where due to its properties, has the potential to be highly mobile, persistent (does not degrade easily) and bioaccumulate within the food chain. It is also a group of chemicals that have the potential for a toxic effect at low concentrations.

The majority of focus in the UK to date has been on two individual PFAS compounds, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). However, the PFAS group of chemicals are thousands in number, and there is still poor understanding over the extent of the full range of PFAS in the environment, as they are not commonly included in potential contaminant testing suites in most site investigations.

An area that needs careful consideration are the implications for the preparation and implementation of techniques and materials used for the investigation and sampling of PFAS in the field. PFAS are a unique set of chemicals that must be treated in a different way by trained and experienced operatives in comparison to more typical suites of common contaminants. Given the potential for their widespread diffuse presence coupled with increasingly low risk screening levels (in some cases in the parts-per-trillion scale), all facets of sample collection and handling require an increased level of rigour to ensure results are reliable and positive identification is not as a result of cross contamination.

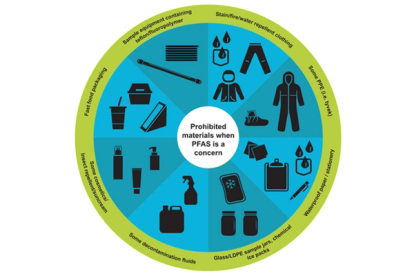

The issue is further confounded by the prevalence of PFAS within consumer products and equipment an operative may typically use on site. For example, PFAS can be present within sun cream, cosmetic products, protective gloves, sample tubing and bailers, personal protective equipment (PPE), waterproof clothing, writing implements and sample bottles to name just a few, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Prohibited materials when PFAS is a concern

The implications of poor quality control (QC) and false positives induced by field or laboratory based cross contamination at best may lead to reduced confidence in results and the outcome of any assessment on which they are based, and at worst may lead to the data set being deemed unfit for purpose and a requirement for re-doing work, leading to time delays, increased costs (PFAS laboratory analysis is costly) and damage to reputation. As such, the data quality objectives for the sampling and investigation of PFAS are of paramount importance.

In order to maintain QC and ensure high quality repeatable results, a specific quality assurance sampling and analysis plan (SAP) should be created to address PFAS specific considerations. It is important PFAS is placed front and centre when considered within the context of a wider land and water quality investigation and work should be carried out by professionals who are competent and experienced in working with this very specific group of contaminants. The SAP should include (but not be limited to):

- Cross contamination mitigation including prohibited items and clothing.

- Sample bottle and sample equipment specification.

- Frequency of trip blanks, field blanks etc.

- Sample storage and transport.

- Decontamination procedures.

It is also important to maintain a dialogue with the laboratory in terms of sampling equipment to ensure that the laboratory data quality protocols are met for analytical purposes.

Whilst the understanding of PFAS may be nascent within the UK, experience gained and expertise developed by our global PFAS team over the last 15 years within North America and APAC places SLR in a prime position to drive quality standards in relation to the development of operating procedures compliant with current best practice. If the presence and characterisation of PFAS is a potential concern in land or water, then it should be approached in a specific way by trained and competent personnel that will ensure that the data quality is maintained and the findings are robust, withstand scrutiny and provide confidence to risk and liability management.

This article is the second in our series of insight articles on PFAS. Read the first article here.

Recent posts

-

-

Driving down carbon in battery supply chains: Why it matters now

by Jasper Schrijvers , Ben Moens

View post -