From insight to action: The evolving story of climate risk assessment

- Post Date

- 19 August 2025

- Read Time

- 10 minutes

Climate risks can affect value chains, portfolios, lending, and insurance through physical risks (e.g. floods, wildfires) disrupting operations and reducing asset value, transition risks (e.g. carbon pricing) increasing the cost of high-carbon operations and increasing liability risks.

As a result, climate risk management has become a matter of fiduciary duty, with institutional investors expecting banks, asset managers, and ultimately companies themselves, to integrate climate risks into their investment processes to further ensure longer-term returns. This is further driven by widely adopted climate-related financial disclosure requirements set out in TCFD and IFRS S2, and then adopted in regulations, such as UK SDR, EU SFDR, EU Taxonomy, EU CSRD, and California’s SB261, etc.

Core to these disclosure requirements is the need to assess climate risk to understand how these could impact the financial performance of investments under different forward-looking climate scenarios. The results of this assessment should then be used to enhance resilience where necessary, e.g. through the adjustment of asset allocations, underwriting policies, mitigation and adaptation investment etc. This article aims to support those that are either beginning to assess climate risks (and opportunities) or are further developing their approach. The intention is to share our market observations, and the lessons learned that can help shape your assessment methodology.

Climate risk assessment trends of interest

Several factors will drive trends in the climate risk assessment space over the next few years, including increasingly specific regulatory requirements, emergence of digital and AI tools, more accurate loss data, and a move towards integrated assessments that consider interconnected issues such as nature-related risk. We see these shaping practices in the following ways:

• Enhanced specificity and granularity: Latest climate-related disclosure standards (e.g. IFRS S2, CSRD) require climate scenario analysis to show the concentration of climate risk and opportunity exposure across both value chains and business models.

The IFRS S2 Sustainability Disclosure Standard on Climate-related Disclosures requires the following:

• a description of where in the entity’s business model and value chain climate-related risks and opportunities are concentrated (for example, geographical areas, facilities, and types of assets)

• the carrying amounts of assets exposed to material risks and opportunities (where there is significant risk of material adjustment

• how climate-related risks and opportunities affect financial position, financial performance, and cash flows.

IFRS S2 and CSRD ESRS require value chain coverage in recognition that risk and opportunity characteristics differ between sectors and geographies, which are determined by the type of products and services and their respective value chains. For example, one value chain sector may be more or less carbon intensive than another, determining the level of exposure to current and potential future carbon prices. This same level of specificity and granularity is even more challenging for asset portfolios, which can be dynamic in nature and lacking specific operational data. This places high importance on the need to screen value chains or portfolios at sector and geography level to identify assets where deeper analysis will most likely add value to risk management decisions and climate resilience.

• Integration of climate considerations: Transition of climate risk assessment from an exploratory, ad-hoc analysis to being fully embedded into ongoing due diligence, risk assessment and portfolio / company strategy, business and financial planning.

This requires approaching risk assessments and indicator selection with a focus on producing decision-useful results which are simple to interpret, as well as thinking about how to build knowledge and confidence within finance, risk, investment, and deal teams so that they can analyse climate risk (capacity building, partnering, tools). There is now a wealth of climate scenario data that aims to estimate future changes to policy, climate, socio-economic indicators, and commodity prices. The challenge is to effectively select and apply these to gain the optimum balance between efficiency, coverage, and insights from risk assessment.

• Climate risk information: Growing maturity in understanding financial exposure, impacts, spread, and balance within portfolios.

This will continue to be driven by insurability as a key trend. Companies will need to contend with whether property & casualty (P&C) insurance will be affordable, or possible to attain at all, depending on the asset’s geography and exposure to significant physical climate risks. This is one of the reasons that climate resilience is now integrated into many asset performance assessment frameworks across all asset life-cycle stages. This is still an area in which financial institutions and corporates are applying a range of different approaches, creating challenges for users of disclosed information.

• Quantifying climate value at risk: High-level and indicative estimations of financial exposure will be used alongside more specific calculations of transition and physical value at risk.

For example, ‘financial effects’ can be measured through the monetary amount of assets or asset revenues, exposed to material risks and opportunities. This is referred to in both CSRD, ESRS, and IFRS. In other words, how much of the business is potentially exposed to a material risk / opportunity. This does not require calculation of cash flow impacts, but rather provides a sense of the scale of potential exposure to an impact. In contrast, a more specific quantification of financial impact can be undertaken by mapping the cause-and-effect relationship (or ‘impact pathway’) between a risk / opportunity and a change in costs or revenues. Calculating these impacts can provide a climate-adjusted cash flow projection, which aids integration into financial planning, stress testing, and risk management decisions.

In addition to methodological developments, we are also gaining a more accurate estimation of disruption and asset value losses from physical hazards. As the quantification of financial effects becomes common practice and impacts themselves become increasingly material, we can expect climate-adjusted value to routinely inform lending, valuation, and underwriting decisions.

The outputs of financial effects quantification trends in corporate reporting, such as growing expectations around climate transition plans, will also provide new insight to investors on companies’ capital investment plans and key sensitivities to the low-carbon transition.

Building effective climate risk approaches

• Right-sized: Approaches to climate risk management need to be right-sized for the institution.

Any overly comprehensive strategy may be overwhelming to investment professionals. Instead, we have seen success when starting with core areas that stakeholders can get behind and building into their processes so they can start to see the value themselves. Hitting the right balance of top down versus bottom up can be tricky for investors. We don’t want a climate risk strategy that is over simplified in order to apply to every company / asset, but we also don’t want to customise the approach for each asset so that the benefit of scale can’t be realised.

• Sequential: Risk assessments often start with high-level top-down screening of hazards across the sectors and geographies in a portfolio.

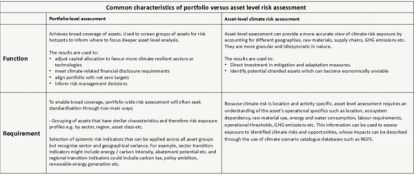

A common challenge for portfolios and value chains that are spread across diverse sectors and geographies, is the need to assess climate risk at different levels of granularity to achieve broad coverage and as well as asset specificity. Portfolio-wide level assessment achieves broad coverage to identify risk hotspots for deeper analysis, ensuring that resources are allocated to priority areas. However, this top-down approach can look at the dataset without context and see risk or lack of risk that is different from reality. Ideally, assets that fall in risk hotspots will then undergo a more detailed asset specific risk assessment considering the underlying operations of the assets during risk assessment, i.e. what happens at the facilities and how their operations would be impacted by a climate event. The table below describes some of the common characteristics of portfolio versus asset level risk assessment.

• Compatible: As deeper analysis is undertaken over time, assessment tools should be compatible in terms of the datasets and analytical decisions taken, which requires an understanding of climate risk indicators and sources of data.

Where scalability has not been considered, results produced with low-resolution data approaches may not be consistent with results once the resolution of that data is increased.

• Clearly specified: Approaches should be designed with outcomes in mind, with a clear definition of the questions of interest and balancing disclosure outcomes, decision-making functionality and analytical effort.

Specifying the outcomes, assumptions, limitations, and functionality helps to manage internal expectations and inform proper use in decision making. This also requires an appreciation of the limitations of current climate risk modelling approaches and where these may fail to adequately inform risk decisions, such as around tipping points, tail events, cascading impacts, and systemic risk.

Acting now will maximise value creation in climate risk assessment

The opportunity is not just in spotting risk, but in building competitive advantage — by knowing where to deploy capital your business will maximise value creation or protection related to climate change. In our work with major corporations, we encourage businesses to view climate risk assessment and screening not as an ESG compliance task, but as a core part of building long-term financial resilience

As we explained, start with mapping your value chain or asset portfolio by sector and location. This will reveal exposure to transition and physical impacts, highlight material activities, and show your dependence on specific sectors and geographies.

There are open-source climate scenario databases, which provide scenario comparisons across a range of physical and transition indicators. These can be used to help interpret and compare how climate scenarios can manifest over time, which is useful in identifying and assessing climate risks and opportunities.

• NGFS IIASA Scenario Explorer: Display of the transition scenarios time series data.

• NGFS CA Climate Impact Explorer: Display of the physical scenarios time series data.

• WBSCD Food, Agriculture and Forests Climate Scenario Tool: Reference scenarios specific to food, agriculture, and forest products.

• WBCSD Energy Climate Scenario Catalogue 3.0 (2024): Explores transition pathways across possible temperature and energy system outcomes.

Advisory Digest

Enjoyed this article? For more like it, get SLR's quarterly sustainable business briefing straight to your inbox.

Sign Up

Recent posts

-

-

Driving down carbon in battery supply chains: Why it matters now

by Jasper Schrijvers , Ben Moens

View post -